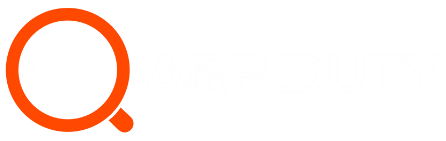

Lemi Ghariokwu, the King of Covers and Visual Rebel Behind Fela Kuti’s Legacy

“We are like warriors fighting for the mental liberation of African people.”

– Lemi Ghariokwu

The king of covers in the rich Nigerian Music History. It’s a rare privilege to sit at the feet of a living legend, especially one who carried the weight of Fela Kuti’s beautiful rebellion in strokes of color, and carved out an entire genre of visual protest, without ever attending a formal art school. But for Lemi Ghariokwu, it was never about the institution. It was about destiny.

And on this particular day, in an interview for The Book, I was privileged to hear him tell it—exactly how it happened.

“I believe strongly in destiny…”

“I became conscious of my artistic talent very early,” Lemi begins, not with pride, but with a calm certainty. “When I was like five, six—I used to draw on the ground. The road where I was born in Agege wasn’t paved, so I’d take broomsticks and draw pleasure cars in the sand.”

He paints the picture in words the same way he would on canvas. A young boy on all fours, drawing dream cars while the world rushed past. One day, a car glided just a foot from his hand before a neighbor pulled him back, scolding him. “But that’s how deep the connection had been,” he reflects.

Despite the pressure from his father, who wanted him to be a mechanical engineer, Lemi never let go of his pencil. “I kept drawing—even in class,” he laughs. “I used to sketch my young, beautiful math teacher in her heels while she taught, completely ignoring the board.”

The Challenge: One Drawing a Day

After secondary school, during the gap before university, Lemi gave himself a challenge: one drawing a day for a whole year. “That was how I became known in the neighborhood. Everyone started calling me ‘that artist boy’.”

One of his earliest commissions came from a military family preparing for a wedding. They had no idea what to gift the officer getting married. “Somebody said the man liked art. So they brought me two photos—one of him in uniform and one of his bride. I redrew them side by side, changed the uniform to lace to match her attire, and presented it.”

It was a hit. Word spread.

Then came a commission from a beer parlour for a Bruce Lee poster. The film: Enter the Dragon. “I painted Bruce Lee, Jim Kelly, and John Saxon. He framed it and hung it up. That poster led a journalist from Punch to me—Babatunde Harrison.”

This was fate.

The Portrait That Changed Everything

“He was drinking in the bar and saw the Bruce Lee poster. He asked, ‘Who did this?’ And someone said, ‘That small boy next door.’ He couldn’t believe it. He came to see me, asked to see my other works, and then saw a drawing I had done of a Fela album—Roforofo Fight—as part of my daily challenge.”

“Can you do album covers?” Harrison asked.

Lemi had already done two, casually, for a band and a musician he met at NTA. But he hadn’t thought of it as a career.

Then came the test. “He said Fela was talking about a new cover two days ago. He said, ‘If I bring you Fela’s picture, can you draw it?’”

Lemi was fired up.

He got the photo, drew Fela’s portrait in 24 hours, and framed it with his mother’s help—she even gave him ₦5 to glass it, a big sum back then. “I used to charge ₦30 for portraits. Mind you, a degree holder earned ₦21 monthly. You could rent a room for ₦4. That gives you the idea.”

When Harrison returned the next evening, Lemi was ready. “He said, ‘You finished already? I gave you this yesterday!’ I showed him, and he said, ‘I’m not going to drink—let’s go. I’m taking you to Fela.”

Meeting Fela: “God Damn It!”

Walking into Kalakuta Republic, Lemi met Fela for the first time.

“He saw the portrait and said, ‘God damn it!’ Then asked for a cheque book and wrote me ₦120. I wasn’t even expecting money—it was a gift! But that cheque gave me value. It told me what Fela thought of my work.”

Lemi refused to take the money. “I said, I give it from the bottom of my heart.” Fela was so moved, he wrote him a gate pass: “Please admit bearer into any show, free of charge.”

That piece of paper? “It was my ticket to Fela shows—and to my professional destiny.”

Breaking Grounds: Alagbon Close & Album Art as Activism

Weeks later, Fela offered Lemi his first official album cover: Alagbon Close. That was 50 years ago.

From there, Lemi would go on to visually narrate Fela’s ideologies, transforming record sleeves into visual manifestos. His favorite? “Zombie.”

“That one was dangerous,” he remembers. “Fela lived right next to a barracks. That album infuriated the military. They attacked Kalakuta, burned it to the ground. A tribunal was set up, and my album cover was used as an exhibit.”

He was on the witness list but never showed. “My mother, she was a seer, warned me not to go. She said she sensed danger. And I felt it too.”

Lemi’s artwork wasn’t just album decoration—it was ideological warfare. With Fela’s permission, Lemi was free to create visual essays that echoed the songs. On the Zombie cover, for instance, he dared to depict soldiers as mindless tools of oppression. It became so controversial that it ended up as an exhibit during a government tribunal after Kalakuta Republic was raided.

“They said we were using innuendo. That was the first time I even heard that word,” he laughs. But behind the humor is sharp intuition. “If I had gone to testify, they would’ve seen me and said, ‘Oh, so this is the boy behind those drawings!’ I would’ve led myself to the slaughter.”

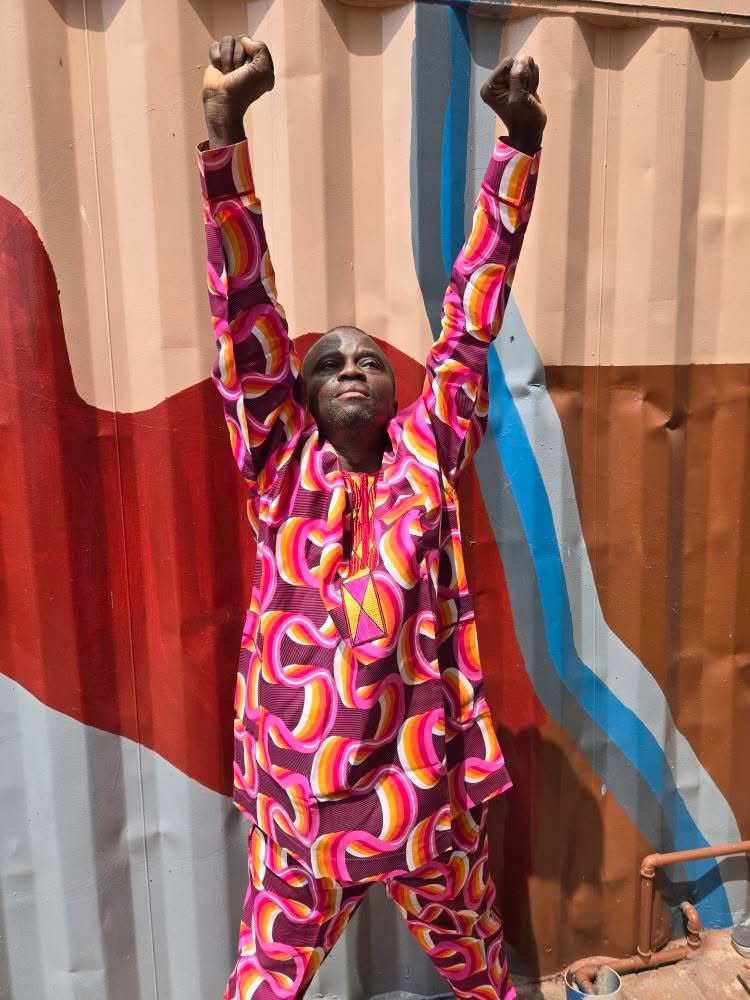

Lemi knew how to survive and how to provoke at the same time. “I’m not aggressive, but I’m a rebel in spirit.”

He escaped what might have been his own abduction by the military.

Cover Art Beyond Fela

Beyond Fela, Lemi designed covers for reggae legends like Ras Kimono and even reissues for Bob Marley’s Talkin’ Blues. “It wasn’t his original record, but my credit is there. I designed the Nigerian reissue for Polygram.”

In 11 years, he created over 200 covers for Polygram Records. “I was a freelancer. I never accepted employment. And that freedom allowed me to reflect my spirit in my work.”

Lemi explains how he added a designer’s column to the back of Fela’s records: Designer’s Comment. “Some covers didn’t reflect the lyrics directly. But the commentary helped fans understand the deeper message.”

He became Fela’s youngest advisor, closest friend, and fellow Pan-Africanist.

Legacy, Ideology & Today

Lemi didn’t just draw Fela’s world—he lived it.

“I am in this society but not of it,” he says. “I play on people’s psychology. I express rebellion with subtlety, not violence.”

When asked about activism today, he doesn’t hold back:

“The problem is mindset. Not protest. These youths want to cloud chase, not change anything. Our minds are messed up by colonial miseducation. Until we shift mentality, nothing will change.”

His heroes? “Peter Tosh, Malcolm X, Thomas Sankara, Marcus Garvey—firebrands who stood for something.”

Now, Lemi spends his days sharing knowledge with Gen Z. “All my friends are young. They ask why I didn’t protest. I tell them, protesting won’t solve anything. It’s a mindset shift we need.”

BALANCING PURPOSE WITH PAY

Despite international recognition—his work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art—Lemi remains grounded. “It gives me fulfillment,” he says. “It’s not ego. I’m totally in control of that. I don’t even like the word celebrity. What are you celebrating?”

He balances ideological work with commercial demands, unashamedly. “Sometimes you need to make compromises. It’s part of life. Compromise doesn’t mean you sold out. Everything has positives and negatives. I know how I’ve navigated.”

A digital artist since 1992, Lemi embraced new tools early. “When NFTs came, I didn’t jump on the bandwagon. But I saw it and said, ‘I’ve been doing this for years.’” His eclectic style allows him to adapt. “I’m self-taught, so I learned from various sources. A journalist once said six different artists must have done those 20 covers. But it was all me.”

ART AS A SOCIAL TOOL

Beyond the brush and canvas, Lemi is a philosopher. A spiritual rebel. A fierce advocate for African consciousness. “We Africans… our journey through slavery, colonialism, and self-colonization has stolen our identity,” he laments. “Our minds have been messed up with colonial miseducation. We mirror the Western world. We wait for them to approve before we feel confident.”

He invokes metaphysics: “Know thyself is the greatest injunction. But most people don’t know who they are.”

He criticizes blind hero worship, especially within religion. “Emulate, don’t worship,” he warns. Instead, Lemi believes in authenticity. “If your role is to make revolutionary art, then do it. If your art is for art’s sake, that’s your role too. But don’t do ‘follow follow.’ There is no competition in destiny.”

ADVICE TO YOUNG ARTISTS

What should young creatives take away? “Know yourself. Listen to the still, small voice within. Find your uniqueness. Stick to consistency, and it becomes your brand.”

He cautions against comparing numbers. “Some people have 10,000 followers and that’s their peak. That’s okay. Don’t compare yourself with someone who has two million. That’s not your path.”

And finally, he offers a personal mantra: “Time is longer than rope. Life grows fonder with hope. We must hold onto hope. That’s what gets us through.”

LEGACY IN MOTION

Fifty years on, Lemi Ghariokwu stands not only as a master of visual art but as a custodian of truth. A griot with a paintbrush. A rebel with rhythm. His journey—from sand drawings in Agege to museum walls in New York—embodies the transformative power of purpose.

In a world of followers, Lemi is a creator of paths.

And the world is still following.

“I’m not aggressive, but I’m a rebel in spirit.”

Interview conducted and written by Andrea Andy